Kijakazi Mashoto is the Principal Research Scientist at the National Institute for Medical Research in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. She is the lead investigator on a project under our Stars In Global Health Program that aims to use novel technology to treat and store water as a strategy to prevent diarrhoea in rural areas of Tanzania.

The lack of access to safe drinking water, together with inadequate sanitation and hygiene, poses a major health risk and is the main contributor to diarrheal deaths globally. Unsafe water supplies cause an estimated 1.734 billion episodes of diarrhea each year and lead to 1.34 million deaths due to diarrheal diseases among children under the age of five years.

In addition, waterborne diarrheal diseases lead to decreased food intake and nutrient absorption, malnutrition, reduced resistance to infection, and impaired physical growth and cognitive development. Diarrheal pathogens are transmitted in several ways, including drinking water and on the hands. That’s why adequate household water treatment and storage practices are important to prevent the disease. It is estimated that 94% of diarrheal cases are preventable through modifications to the environment, including interventions to increase the availability of safe water, and to improve sanitation and hygiene. Household water treatment and safe storage (HWTS) have been shown to reduce diarrheal morbidity by 39 to 70%.

On this World Water Day, I wanted to highlight the plight many Tanzanians face regarding access to water, as well as discuss an innovative approach that we are providing to help alleviate the problems associated with lack of access to clean water.

Lack of access to improved water sources is a major problem in both rural and urban Tanzania. Less than half of the rural population in Tanzania has access to safe drinking water. Many people rely on water from unsafe sources, such as ponds, rivers and streams. Such water is rarely treated, due to a lack of awareness and, to some extent, poverty and scarcity of fuel wood to boil water. A number of studies have shown that water in rural areas in Tanzania is sometimes contaminated at the source. But even when water is deemed safe for drinking at the source, it is commonly re-contaminated during collection, storage and use at home.

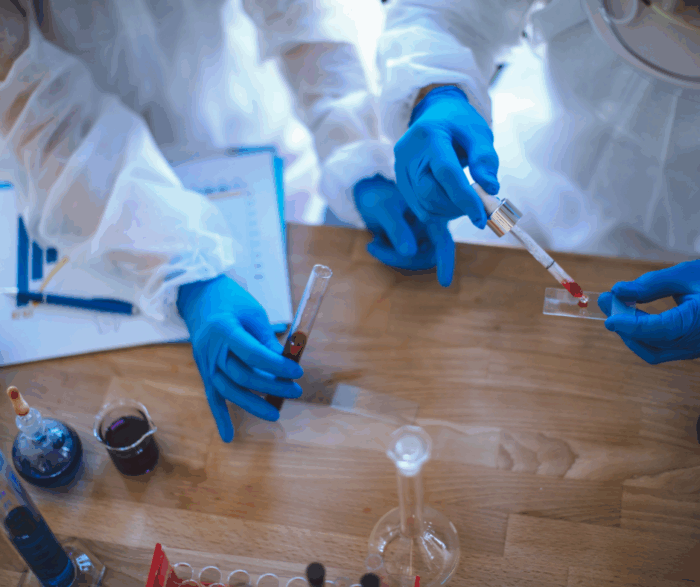

With the support of Canada and Grand Challenges Canada, we wanted to test the effectiveness of a water disinfectant called Takasamaji and the safe drinking water storage containers that go along with it. We felt that this new, simple technology could help to prevent diarrhea among under-fives.

We distributed Takasamaji and the safe drinking water storage containers in five out of ten Mkuranga villages in Tanzania. In a year’s time, 243 households accessed and tested this simple technology, representing 1,094 people (of which 406 were children below the age of five). A total of 78 local community members were recruited to distribute Takasamaji and to collect information on diarrhea on a weekly basis for a period of 17 weeks. Experts from the Ministry of Water in Tanzania assessed the quality of water consumed by the villagers before and during the implementation of the project.

Overall, the water storage container was well accepted, liked and preferred by the households taking part in the project, especially the fact that children could also collect the water without the help of adults.

While the quality of household drinking water treated by Takasamaji improved, it did not reach the required national standards. Takasamaji reduced bacterial contamination by 80% and turbidity levels by 70%.

For 17 weeks, we closely followed a total of 713 children (mean age 2.2 years, 53% girls) to record their episodes of diarrhea. In this large group were 406 children under the age of five years that belonged to households accessing the technology for water treatment and storage, while 306 children lived in households not taking part in the intervention. Before the start of the project, the seven-day period prevalence of diarrhea in children in households that would access the technology was similar to the numbers in households that would not have access to the technology (6.1%). Within the 17-week timeframe, the prevalence of diarrhea differed between children in households accessing (7.3%) and those not accessing the water treatment technology (14.8%). On average, one case of diarrhea per 10 children per week was reported before the intervention. After the implementation, this number was reduced to 0.22 episodes per 10 children per week. Significantly fewer diarrhea cases were reported for children in the intervention arm (73) compared to those in control arm (190 episodes).

Children in households accessing Takasamaji were less likely to experience diarrhea compared to those who did not have access to Takasamaji. Takasamaji and the safe storage drinking water containers were effective in reducing episodes of diarrhea among under-fives by 54%. When other factors (such as poor socio-economic status, lack of WASH education and use of unimproved water sources) were considered, intervention reduced the episodes of diarrhea by 49%.

Talking to villagers, we learned that the community was happy that the simple technology helped to prevent episodes of diarrhea in children below the age of five years.

“Water treated with Takasamaji has good taste; my family and I used it but we did not see any difference between the water treated with Takasamaji and untreated one; I found the water tastes are the same.”

– A member in a Focused Group Discussion, mixing females and males, Nyamatotipo

“To be honest, even food has different taste before and after cooking; so you cannot expect the water to have the same taste before and after treatment. For me, I saw the slight difference in taste, but it is not bad; it cannot discourage a person to use it.”

– A man in a Focused Group Discussion, Nyatanga

In conclusion, Takasamaji and the safe drinking water storage containers for simple household water treatment reduced episodes of diarrhea among children under the age of five years by 54%. Takasamaji was able to improve the quality of water in five villages of the Mkuranga district. However, in order to improve the quality of drinking water to the national recommended standards, it is imperative to optimize the improve the formula of Takasamaji for scaling.

We encourage you to post your questions and comments about this blog post on our Facebook page Grand Challenges Canada and on Twitter @gchallenges.