Dr. Aliya Naheed is an Associate Scientist at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b). She is currently carrying out innovative research to promote food safety among street vendors in Bangladesh.

Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, has seen one of the highest urban growth rates in recent decades and will be the third largest city in the world by 2020. About 15 million people call it home and street food is a very popular event in the daily life in Dhaka. It is an essential source of food and nutrition for people with a low income. With the rapid increase in Dhaka’s population, the street food business has also been expanding rapidly, including the rise of the unregulated street food sector. There have been calls to implement appropriate strategies to make sure street food is safe for consumption for the large number of urban dwellers that eat at these stalls in Dhaka every day. Over the past few years, the link between food safety and health concerns has become a public topic globally and, as in many developing countries, street food has become a health concern in Bangladesh as well.

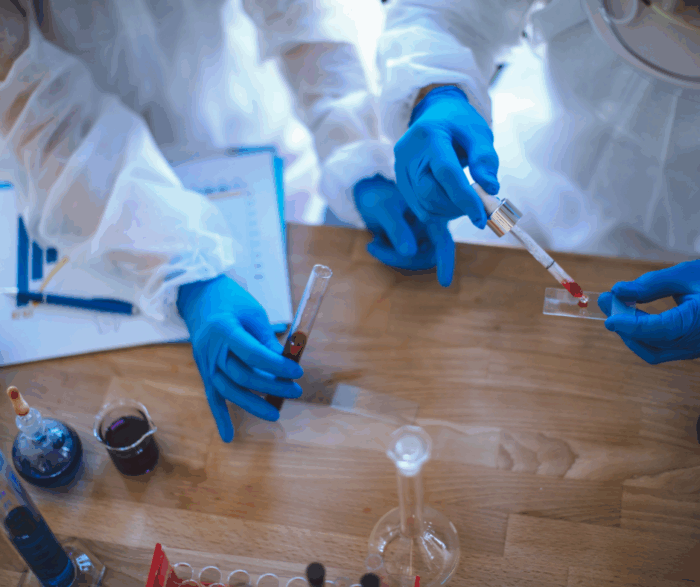

In 2013−2014, Grand Challenges Canada supported an intervention for promoting street food safety in Bangladesh, a first in the country. The grant aimed to improve knowledge about safe handling of food among street food vendors, reduce the concentration of microbial contamination in street food through good hygiene practices, and reduce contamination by promoting hand washing with street vendors. Instead of attempting to apply a brand new innovation, the intervention adopted the World Health Organizations’s Five Keys to Safer Food programme and developed a behavioural change communication intervention; 100 street food vendors in Dhaka city were provided with safe food handling training and were offered a low-cost, plastic water jar made of food grade materials to safely dispense water. Water purification tablets for storing treated water at the vending site were also offered as a way to promote the use of potable water in every step of the process. Additionally, liquid soap and hand sanitizer were provided in order to promote hand washing among street food vendors. Surveys were conducted before and after implementing the behavioural change communication intervention and we tested samples of street food and hand rinse for assessing microbial quality of street food and improvement in hand hygiene.

Before the intervention, numbers revealed that 52% of street food was contaminated with coliform and more than 37% was contaminated by faecal pathogen (E.coli). After the intervention, we found that 42% of the samples were contaminated with coliform and about 29% were contaminated by faecal pathogen (E.coli). Similarly, before the intervention 88% of the hands of street food vendors showed contamination with coliform, while 62% of vendors carried faecal pathogen on their hands. After the intervention, the hands of 79% of street food vendors were contaminated with coliform and only 36% of the vendors carried faecal pathogen on the hand while preparing street food.

Overall, these numbers suggest that the behavioural change communication intervention has improved the personal hygiene of street food vendors and made street food safer. This also indicates that the intervention has a huge potential to improve food quality, as long as the vendors have minimum access to basic infrastructures.

The intervention has demonstrated a positive impact in a small population within a short time span. The next step will be to document that this technique to maintain street food safety can be implemented in a large population setting and for the long term. If the larger-scale intervention can produce positive impact on street food safety in Dhaka, it would have the potential to directly reduce food and water borne diseases in urban settings. However, this will require government support by creating regulatory mechanisms for providing food safety training among a large group of street food vendors all over Dhaka. The city would also have to develop an effective monitoring and enforcement system for hygienic practices.

On the top of that, consumers must play a crucial role in making street food safer. Increased awareness and a clear demand by consumers for safe street food will be essential incentives for promoting safe street food handling practices among street food vendors.

Overall, interventions targeting street food vendors are challenging and the demonstrated successes are rarely documented in a developing country setting.

The support of Canada and Grand Challenges Canada has set an extraordinary example. It showed that a relatively small amount of funding invested in the right people can render great success for a challenging yet important project. These types of grants can inspire researchers from developing countries, particularly women, to aim for Bold Ideas with Big Impact.

While urbanization has been growing very fast in Bangladesh, street food will grow as a much bigger industry than it is now, as in many other countries who have graduated from a low-income status to a middle-income status. Hence, safety of street foods will be a future challenge for both the health sector and the food sector unless timely, appropriate measures are effectively implemented for institutionalizing street food safety by the relevant authorities. This calls for support from the government of Bangladesh and donor agencies for conducting large-scale food safety research, in order to find sustainable solutions that can meaningfully contribute to the future implementation of food safety law in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

We encourage you to post your questions and comments about this blog post on our Facebook page Grand Challenges Canada and on Twitter @gchallenges.