Shahreen Reza is the founder of PurifAid Water International Inc., a Canadian social enterprise that deploys water purification units at the community level in rural Bangladesh. PurifAid is supported by Grand Challenges Canada through the Stars in Global Health program.

This week, thousands of individuals and hundreds of organizations from around the world are gathering in Stockholm for World Water Week. The theme, Water for Development, reflects water’s prominence on the global development agenda.

In Bangladesh, the scale of the challenge of providing safe drinking water and governing the common environment is particularly vivid. In a country where everyone outside the cities draws their water from tubewells, 75 million people are at risk of contamination from arsenic and other metals that occur naturally in the subsoil. Since Bangladesh’s arsenic problem was first discovered in the early 1990s, efforts to raise awareness and provide access to safe water sources have failed to make much of a dent in the number of people exposed. This contamination crisis, which the World Health Organization has called “the largest mass poisoning of a population in history,” leads to one in every five deaths in the country today.

From Scotch whisky to arsenic

The catalyst that ignited the project came in 2010 while I was a graduate student at Sciences-Po, Paris, working on a Boston Consulting Group competition about marketing Scotch whisky in the developing world. I came across a scientist, , Dr. Leigh Cassidy, who had invented a way to use a whisky by-product to purify water cheaply and easily. In my mind, it clicked: here was something cheap, easy to use, and capable of removing arsenic from groundwater. In the end our business case didn’t win the competition – but the idea did not go away.

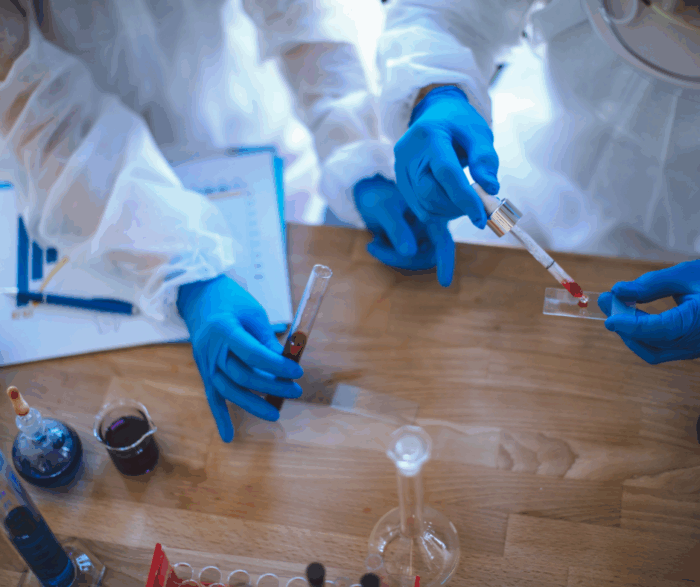

I put together an international team who were also taken in by the cause. In 2014, we had a breakthrough when, with the support of Grand Challenges Canada (funded by the Government of Canada), and in partnership with BRAC and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, we were able to do a proof of concept with four prototypes of the water filter in the Matlab region of Bangladesh.

Our equipment is simple: the filter fits onto pre-existing tubewells and brings arsenic levels down by 80 to 95 percent. The challenge remains how to create a sustainable model for paying for, deploying and operating the filters. In the past, many drinking water projects have failed, not because of the technology, but because the filters were not being properly used or maintained. Furthermore, a project to provide clean water cannot rely on donor money indefinitely. Yet, for all the urgency of the problem, few of the villagers we interviewed were willing to pay for purified water. Arsenic is invisible, odourless, and often takes several years to produce symptoms. Many people consider that they have more urgent things to spend their time and money on.

Lessons learned

What they do wish to spend money on is convenience. We returned to Bangladesh in January 2015 and learned that there was a far greater willingness to pay for piped water systems. PVC piping would be a far more convenient means to deliver filtered water to a surrounding cluster of homes than retrofitting our filter to single unit tubewells. One of our engineers, Steven Honan, came with us and mapped out a delivery system.

Along with this lesson, another development occurred. During our pilot, we were contacted by a garment factory owner who had learned about our filter and was interested in if it could decontaminate industrial wastewater.

The booming Bangladesh textile and garment export industry is powering the country’s growth and providing livelihoods to five million workers, mostly women. The household brands that we have in our closets in Canada – H&M, GAP, Calvin Klein, and Levi’s, to name a few – all sell t-shirts, jeans and tops made in Bangladesh. Yet it is environmentally unsustainable: the garment industry draws 1.5 trillion litres of groundwater every year from Bangladesh alone, resulting in the water table falling drastically over the past decade. Meanwhile only one in four factories has adequate water treatment systems – the rest release the highly contaminated water directly into rivers.

Most of the workers in the textile factories come from nearby villages, where they are exposed to arsenic contaminated drinking water. Many get sick, which leads to 7-12 million lost working days a year, without counting all those who cannot stay away from work even if they are ill, and are much less productive as a result.

It seems that the best way to attack the twin challenges of wastewater management and unsafe drinking water is with a connected initiative: on one hand, to help factories drastically cut their wastefulness, on the other, to provide cheap and sustainable drinking water systems to their employees and their communities.

PurifAid has come far over the last two years, and is ready to take the next step by testing our social enterprise delivery model. Through tackling one of the biggest water crises in the world, we are part of something much bigger. The consequences go beyond Bangladesh, extending to the way we produce goods and mana

ge water resources worldwide. I am encouraged by the growing focus on water resources and wastewater management, including from private investors – such as Tau Investment Management – who are turning their attention to cleaning up the garment and textile industry.

Troubled waters ahead

Two decades and many efforts later, 75 million people in Bangladesh still lack access to safe drinking water. In the same space of time, the country’s textile and garment industry has become both a vital pillar and a looming threat to nature and public health. Facing both crises will require innovative and collaborative solutions – two values championed by Grand Challenges Canada, celebrated in World Water Week, and guiding PurifAid.

If these are your values too, you can help the cause by liking our page on Facebook and sharing our updates with your network.

Read Ammara Niyaz’s blog post for World Water Week 2015: Canada is funding innovations to improve water quality in the developing world

We encourage you to post your questions and comments about this blog post on our Facebook page Grand Challenges Canada and on Twitter @gchallenges.